Climate Change Reduces Nutrients In Food

Increased CO2 emissions make some foods less nutrient dense. The phenomenon can cause an increase in nutritional deficiencies and health problems around the world.

No one is safe from the consequences of climate change. The process affects the entire planet and is one of the greatest threats to the future of humanity. The main cause of the increase in temperatures is the increase in the proportion of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, which is not only causing droughts, fires, floods or loss of biodiversity, but is also reducing the nutritional quality of food.

The so-called “nutritional cost of climate change” is a rarely talked about side effect, but its consequences can be disastrous due to increasing nutritional deficiencies and the health problems they cause.

Climate change is linked to health problems: longer and more intense allergy seasons, the spread of mosquito-borne diseases such as Zika and malaria, and even the escape from ecosystems of potentially pandemic viruses for humans.

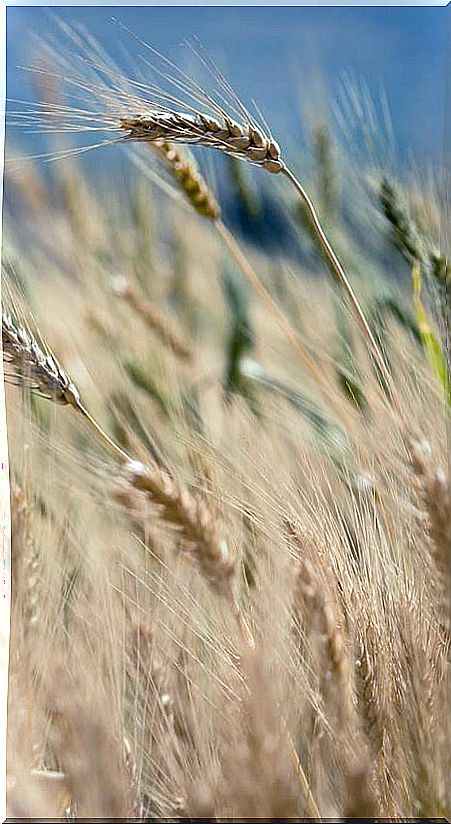

As if all that were not enough, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) of the United Nations Organization warns in one of its reports that global warming decreases the nutritional value of important crops such as wheat and rice.

More CO2 in the atmosphere: more carbohydrates and less protein

The explanation is that high levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere (we have already reached 415 parts per million, 28 percent above the 350 ppm considered safe) alter the internal chemistry of plants in such a way that it decreases the proportions of proteins and essential nutrients such as the minerals zinc and iron and the vitamins of group B. This phenomenon would aggravate the situation of the more than 800 million people who already suffer from malnutrition.

Researchers have found that the composition of plant tissues requires a delicate balance between carbon dioxide in the air and nutrients in the soil. Plants use carbon dioxide (CO2) as a fuel for photosynthesis, which transforms sunlight into chemical energy, but the more there is no better. At least it is not for the people who are going to eat the plants.

Not all crops react the same. The report details that rice and wheat, two of humanity’s essential food crops, carry out photosynthesis of the “C3” type (so called because plants produce molecules with three carbons). Potatoes and almost all fruits and vegetables carry out this type of photosynthesis and are, therefore, among the most affected. Other plants, such as corn, carry out “C4” type photosynthesis (four-carbon molecules) and are somewhat less affected.

When a plant with C3 photosynthesis absorbs too much carbon dioxide, the proportion of carbohydrates in its composition increases and the concentration of proteins and essential micronutrients such as vitamins and minerals is reduced. This happens because plants reduce their ability to absorb nitrates (the most common type of nitrogen in the soil) and convert them into organic compounds such as proteins.

An unknown phenomenon until recently

Molecular biologist Irakli Loladze, from the Bryan College of Health Science, in Nebraska (United States) is surely the scientist who has studied the phenomenon the most. He started researching it 20 years ago but did not get to publish anything until just 4. According to Loladze, there is a direct link between the increase in carbohydrates in vegetables and the growing epidemics of diabetes and obesity in the world: “The increase in levels CO2 has already altered the quality of our food. “

All this process adds to the loss in the nutritional content of foods over the last few years due to the use of fertilizers in intensive agriculture. Farmers have favored rapid growth and yield regardless of nutritional outcome, explain Samuel Myers, professor of public health and researcher at Harvard University. “We cannot interfere and reconfigure most of our planet’s natural systems without encountering unintended consequences,” he adds.

The loss of nutritional quality of plant foods will be reflected in the medium and long term in the health of the world population. A study cited in the IPCC report predicts that when CO2 levels reach 500 parts per million by 2050, 200 million people will be deficient in zinc.

Zinc deficiency increases vulnerability to viral and bacterial infections and can lead to diarrhea, poor vision, ulcers in the mouth and stomach, and even psychological and cognitive disorders.

The iron content of foods is also being reduced, which will aggravate the extent of a nutritional deficiency that is already the most common and that can cause various problems such as fatigue, hair loss and weakened immune function.

Two billion people already suffer from low levels of zinc and iron and the situation will get worse in the future. “It is a huge burden on global health,” Samuel Myers wrote in an article published in the scientific journal Nature .

Another study indicates that 18 countries could lose more than 5% of the dietary protein provided by rice and wheat crops by 2050. The data is serious because 600 million people in the world obtain most of their calories from rice.

76% of the world’s population currently get most of their daily protein from plants. As the proportion of this nutrient is reduced due to climate change, hundreds of millions of people will see their intake decreased. This is an especially significant risk for the more than 350 million children under the age of 5 who live in countries in Africa and Asia and who already suffer from high rates of protein deficiency.

The selenium content in food is also going to be reduced. It is an essential nutrient for the functioning of the immune system that also has antioxidant properties and prevents cognitive deterioration. A lack of selenium is also known to inhibit the proper growth of children’s bones in some selenium-deficient areas of China.

Currently, one in seven people is deficient in selenium, and the incidence is growing. A recent study by Harvard University predicts that, as a direct consequence of climate change, 66% of farmland will lose 8.7% of its selenium.

Several threats weigh on the global food system

Agriculture and livestock are both responsible and victims of global warming. Both activities produce 37% of total greenhouse gas emissions. In fact, one of the main IPPC proposals to combat climate change is to reduce the proportion of meat in the diets of the richest countries, so that the land is used to directly feed people, not livestock. It is also desirable to reduce the transport of food and favor the consumption of local foods.

But the changes that should take place in the global food system will be complicated by the loss of nutritional quality of food and by changes related to climate change, such as storms, heat waves and droughts, which can potentially damage crops. and cause price rises. The combination of all the above factors, which are happening at the same time, will make it more difficult to feed a world population that is also growing, according to Cynthia Rosenzweig, co-author of the IPPC report.

Less diversity, less food

Not only changes in atmospheric CO2 levels can alter the quality of human food. Climate change is causing the disappearance of birds, bees and other insects responsible for the pollination of plants from which food comes out, which could cause a problem of malnutrition in many parts of the world, according to a study led by Dr. Samuel Myers, from Harvard University (United States).

The most important insects for pollination and whose populations are decreasing are bees, wasps, moths, butterflies and beetles, but there are also animals that carry pollen such as hummingbirds, fruit bats or megachiropterans, foxes flying or pteropus bats, possums, lemurs and geckos.

Researchers say that if pollinating animals disappear, more than 70 million people in resource-poor countries could be deficient in vitamin A, and more than two billion people who already consume less vitamin A than recommended would have serious nutrition problems .

In the case of folic acid, more than 170 million people would suffer a significant deficit and more than one billion would be affected by the shortage of foods rich in this nutrient.

In total, worldwide supplies of fruit would be reduced by 23 percent, vegetable supplies by 16 percent, and nut and seed supplies by 22 percent, according to the study’s estimates.

The study was conducted by analyzing the resources of 224 types of food in 156 countries, and the vitamins and nutrients of the foods that depend on pollinating animals were quantified. With these data, the nutritional deficits that world society would face were estimated if these animals were to go extinct.

All this would generate changes in the diet of society that could increase death from chronic diseases or malnutrition problems in more than one million deaths worldwide, which would mean an increase in mortality of approximately 2.7 percent.

How much will the nutrients be reduced?

- Wheat to be grown in 2050 will contain 9.3% less zinc, 5.1% less iron and 6.3% protein.

- Rice will provide 3.1% less zinc, 5.2% less iron and 7.8% protein. In addition, the proportions of group B vitamins will decrease between 17 and 30%.

- The corn will contain 5.2% less zinc, 5.8% less iron and 4.6% less protein.

- Soybeans will be 5.1% poorer in zinc and 4.1% in iron. It will slightly increase the proportion of protein.

Source: Nature .

Scientific references:

- Samuel Myers et al. Rising CO2 threatens human nutrition. Nature .

- Samuel Myers et al. Effects of decreases of animal pollinators on human nutrition and global health: a modeling analysis. The Lancet.

- Chapter 5 on food safety of the IPPC report.